By Judithe Registre, Founder and Podcast Host

Image source: Pixabay

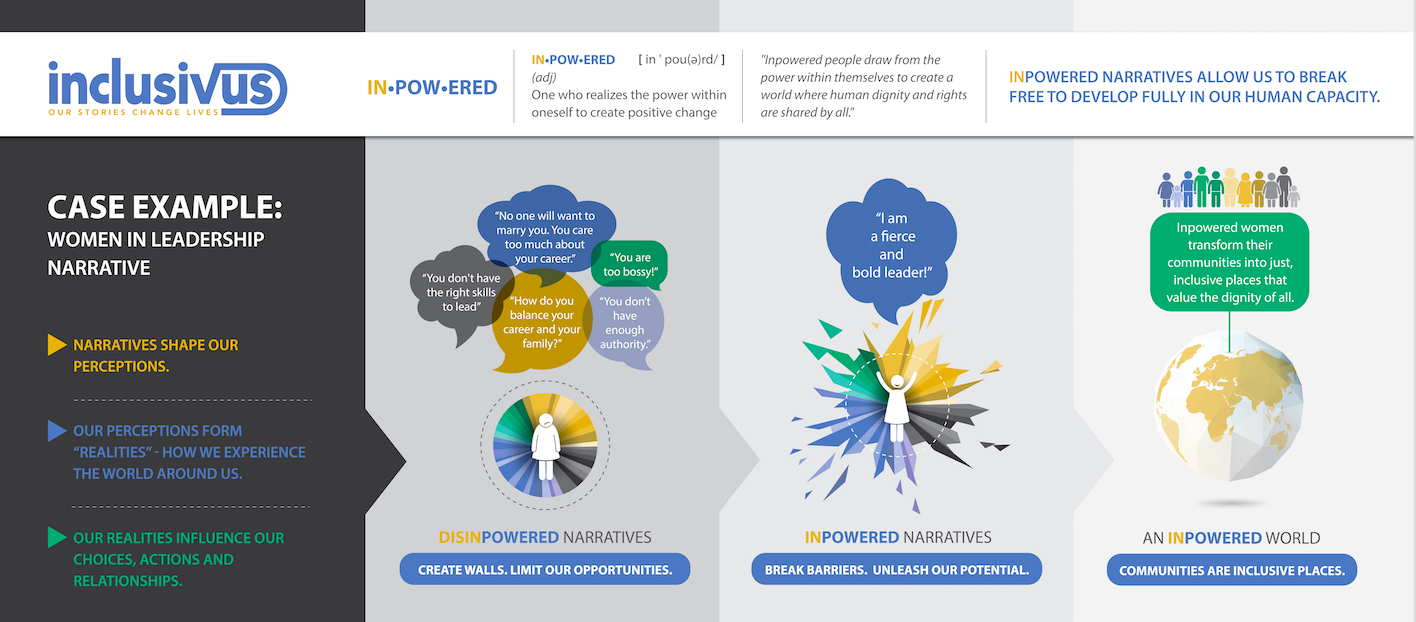

What is a brand? A brand is what we think about when we think about a product or a company. In the simplest terms, a brand is an image of a company, product, person, or place. It is a collective perception that is held by all.

In the age of social media, the idea of a brand has extended to individuals. Think about your own social media presence. How are others perceiving you when they see your profile? This is your brand. When we think about a brand, we think about the value, the character, the culture of the branded item, whether it’s a product or a person. A brand is a value proposition for how we choose to engage with a particular product, person, group, or place.

Countries have long understood the importance of branding. For instance, the Nordic countries recently launched a design strategy to develop their own brand. Countries like Japan and Rwanda have employed similar strategies to manage their brands. Countries, just like companies, strategically design brands in order to form public opinions of them. But historically excluded social groups and communities do not have that opportunity, nor do we as a society have the understanding of the need for branding as essential to social progress. Yet still, historically excluded communities, marginalized communities, and indigenous communities are branded—just not by their own design.

Consider the studies that have shown that Blacks and Latinos feel misrepresented by the media. The data on media representation of Blacks and Latinos confirms that sentiment. Consider also the brand of black men, women, and children. According to the US Department of Education Office for Civil Rights, “black students are suspended and expelled at a rate three times greater than white students. On average, 5% of white students are suspended, compared to 16% of black students.” This is devastating considering that in most of these cases, black students are not misbehaving or posing any threats, certainly not at a rate three times that of their white counterparts. Rather, teachers and school administrators are perceiving black children as threats based on the brand that has been formed around them, which leads to the unfair and unjust persecution of these kids. The brand around Black Americans as being troublesome is so pervasive that black children are not allowed the same opportunities in experiencing childhood as white children. They are treated based on the particular framing of the Black American narrative, not because of who they are and the value they hold, but because of the way outside groups have constructed this narrative.

Five elements of brands

According to aytm.com, there are five elements to a brand. When we consider these five elements as they relate to communities, we will see how brands are intrinsically linked to communities and social groups and how the concept of branding, when effectively used and applied, could be leveraged to advance social progress.

- A brand is a promise. A brand is a promise that tells the consumer what they are going to get. If communities were allowed to formulate and intentionally create their own brands, we would probably receive drastically different images of countries than the ones we see currently. For too many communities, what are now being expressed as brands are nothing but stereotypes that were created by outside groups.

- A brand is a public perception. Think of the perceptions we have toward immigrants or Muslims, compared to those we have about white men. On the whole, it’s probably fair to say that our perceptions of immigrants or Muslims are more negative than our perceptions of white men. What if all communities had the opportunity to create perceptions of their communities that were actually in line with their true humanity? For example, what if we saw the black community as as culture of richness, a culture of wealth, a culture of intelligent, dynamic people, a culture of brilliance. We would see and engage with this community differently, and they would experience their own worlds differently.

- A brand has expectations. Our perceptions shape the expectations we have of these groups. Whether or not these expectations are logical, and whether or not it’s fair of us to hold them, they exist. The problem, though, is that these expectations do not simply exist within our own minds, they also play out in the real world.

- A brand has a persona. Just like people, brands have personas and personalities. This is one of the most important elements of brands and their links to communities. Consider Nike. When we put on a pair of Nike shoes, we think about being athletic—we actually feel more athletic—all because of the brand’s persona. The persona of the brand not only affects the branded item (or group) itself, but also our relationship to it. When the branded item is a community or society, this can be extremely problematic.

- A brand has elements. The elements described above are intrinsically linked to our engagement and relationship with the product, in this case the community.

Communities all have brands. Social progress, including gender justice, racial justice and economic justice, relies heavily on community branding. In order to achieve positive social progress, we need to see positive messages about communities.

What if communities and social groups could design their own brand perceptions?

Imagine if Nike were to let Adidas run its marketing department. That is essentially what’s happening when one group of people determines the brand of another.

What if we were to start investing in communities to build their own brands? Brands that truly reflect who they are, what they’re about, what they stand for, what they value. Would relationships across different groups be different? Would public perceptions of groups be more affirming? I bet they would. If countries were to start building and designing their own brands, all of us would begin to see the humanity of everyone, across all communities and countries, and the mirror reflections we have of each other. We all want the same things: We want to be loved, we want to be heard, we want to be understood, we want to be respected, we want to have and create opportunities for our children, we want to live in a world with peace and stability. Ideas of Muslims by non-Muslims would be different, ideas of African-Americans would be different, ideas of women would be different, ideas of men would be different. We would have a more holistic view of each other. We would move beyond stereotypes and caricatures.

My challenge to all of us working in the social sector and working to advance social justice in all of its forms is to ask ourselves: What is the brand proposition of communities that we are serving? What are the perceptions, promises, and expectations that we hold of different social groups? And what would we like those brand propositions or brand elements to be?

This is a challenge and an opportunity for all of us who work to serve communities, but it’s also a challenge for communities themselves. As members of communities, we must ask ourselves what it would take for us to build our own brand and how much time would it take to do so, to transform how we exist and how we are being in the world, and how the world is being with us. This is no simple undertaking. It would be costly. Whatever the cost, it would be worth it as it would position us to accelerate progress, have inclusive societies and expand opportunities. Is this an area that the social sector—including foundations, philanthropists, and governments—should invest in?

Imagine a world where we live in balance with one another with an honest and fair perception and understanding of each other. Could we fundamentally alter the negative perceptions of historically excluded communities and population to move towards a world with more peace, compassion, and justice for all? Could rebranding of communities affect social progress? What do you think?