By Tiziana Kassahun, Strategic Designer

Photo credit: Stefano Deluigi

As soon as people find out that I wrote a book called Architecture and Human Rights, they immediately ask me two questions: 1) Why? and 2) What do the two have to do with each other?

Allow me to explain.

Why human rights and architecture?

First, why did I write a book titled Architecture and Human Rights?

“Human” and “rights” are two of the words that I most respect and love. They belong to everyone, everywhere, and belong to each of us simply by virtue of being human.

The word "architecture" comes next. Architecture is the physical manifestation of our relationship with each other and the natural world. Architecture may not seem to relate to human rights, but at its core, architecture is intrinsically tied to humanity. I believe architecture is revolutionary because it has the ability to reinvent the way we live and exist together.

What does architecture have to do with human rights?

Before we can understand how architecture and human rights can work together, we need to understand them separately.

First, let’s talk about human rights. How can universal human rights exist?

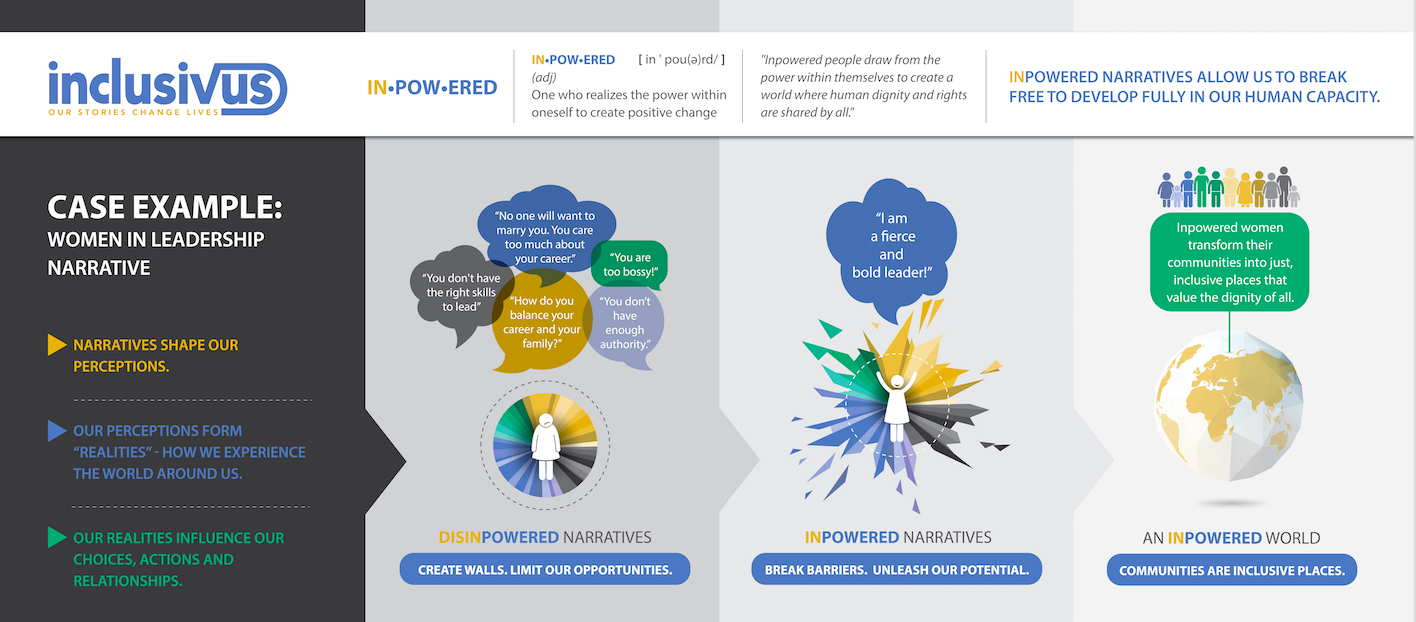

Generally, when we think of human rights, we think of those rules, both written and unwritten, that are set forth as norms of national and international law, created through judicial decisions and enactments. But there is another side of human rights, another way that human rights are determined: Through those unspoken, everyday actions, rules, and institutions that we hardly even notice. One of these is architecture.

If you’ve never considered human rights and architecture to be so linked, you’re not alone. Most people think architects design buildings and cities, which has no bearing at all on humanity as a whole. But really, what architects truly design are relationships. Buildings and cities are designed for people and they impact how we relate and co-exist.

Architecture is anything we can think of which will transform a space into a place where human beings live. Without architecture, I fear I would not be able to find my way across a room; nor would I know how to conduct myself in many circumstances. Architecture helps us to navigate situations and feelings we may never realize. It is about building relationships through the alteration of space.

Architecture can easily become a “me” space. It is a place for individualism, for people’s nascent and by now overwhelming urge to claim space for themselves, and to claim that space from others, from society, and from the state by emphasizing privacy over communalism and denying strangers access to our communities and their resources. This is problematic for humanity and for human rights. By encouraging the emphasis on the self over the community, we are allowing ourselves to forget the rest of the world, which in turn allows for the neglect of human rights.

Accepting this type of neglect—accepting eviction, or rights deprivation as inevitable, or as alright as long as it gets things done faster—is horrifying, and I wouldn't want to live in a world where that's the norm.

But architecture can also be an “us” space. It can create places for everyone. As much as it has the potential to make places smaller and more centered on the self, it is also capable of turning formerly me-centered places into places that encourage communalism and togetherness.

For the sake of our kids, for the for the sake of our communities, for the sake of our future, let's stop mindlessly constructing and start talking about how we can build mindfully. Let’s start talking about rights and architecture.

As a species, we are now at a crucial time. More than fifty percent of us now live in urban areas, and that number is only going to increase. Over the next two decades, we will face a transformation that will determine whether the next 100 years is the best of centuries or the worst of centuries.

In the context of such transformation and everything that comes with it—great social changes, ethnic conflicts, urban inequalities, environmental threats and economic problems—what does architecture mean? The answer is a widespread sense that much of what we have built cannot be tolerated because at the root of the human rights concept is the idea that all people should be able to live with dignity. Much of our current architecture, and our beliefs about architecture, does not support this.

We are bogged down in a morass of multicultural conflict, and lagging the global innovation marketplace. This is the time we live in. We must choose to be city developers, we must choose to make cities sustainable. And this is where architecture and human rights are a necessity. If we start looking at architecture as a vehicle to advance human rights, we could be on our way to solving some of our largest, most urgent problems. My book, Architecture and Human Rights, provides unique ways of experiencing and reframing architecture—a perspective that could solve some of our largest most urgent problems.

The future of our cities is practically the future of our humanity. We must take care of our cities, and start building mindfully rather than carelessly, in order to advance humanity in the most positive way.

Photo credit: Stefano Deluigi